M*A*S*H (TV series)

| M*A*S*H | |

|---|---|

Title screen

|

|

| Genre | Comedy-drama |

| Based on | M*A*S*H: A Novel About Three Army Doctors by Richard Hooker |

| Developed by | Larry Gelbart |

| Starring | Alan Alda Wayne Rogers McLean Stevenson Loretta Swit Larry Linville Gary Burghoff Mike Farrell Harry Morgan Jamie Farr William Christopher David Ogden Stiers |

| Theme music composer | Johnny Mandel (written for the film) |

| Opening theme | "Suicide Is Painless" |

| Ending theme | "Suicide Is Painless" (big band version) |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 11 |

| No. of episodes | 256 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) |

|

| Location(s) | Los Angeles County, California (Century City, Malibu Creek State Park) |

| Camera setup | Single-camera |

| Running time | 30 minutes with commercials, except "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" (2 hours with commercials) |

| Production company(s) | 20th Century Fox Television |

| Distributor | 20th Television |

| Release | |

| Original network | CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) |

| Original release | September 17, 1972 – February 28, 1983 |

| Chronology | |

| Followed by | AfterM*A*S*H W*A*L*T*E*R |

| Related shows | Trapper John, M.D. |

| External links | |

| Website | |

Contents

Plot

M*A*S*H aired weekly on CBS, with most episodes being a half-hour (25 minutes) in length. The series is usually categorized as a situation comedy, though it is also described as a "dark comedy" or a "dramedy" because of the dramatic subject material often presented.[a]The show was an ensemble piece revolving around key personnel in a United States Army Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) in the Korean War (1950–1953). (The asterisks in the name are not part of military nomenclature and were creatively introduced in the novel and used in only the posters for the movie version, not the actual movie.)[clarification needed] The "4077th MASH" was one of several surgical units in Korea.

As the show developed, the writing took on more of a moralistic tone. Richard Hooker, who wrote the book on which the television and film versions were based, noted that Hawkeye's character was far more liberal in the show than on the page (in one of the MASH books, Hawkeye makes reference to "kicking the bejesus out of lefties just to stay in shape"). While the show is traditionally viewed as a comedy, many episodes were of a more serious tone. Airing on network primetime while the Vietnam War was still going on, the show was forced to walk the fine line of commenting on that war while at the same time not seeming to protest against it. For this reason, the show's discourse, under the cover of comedy, often questioned, mocked, and grappled with America's role in the Cold War.

Episodes were both plot- and character-driven, with several episodes being narrated by one of the show's characters as the contents of a letter home. The show's tone could move from silly to sobering from one episode to the next, with dramatic tension often occurring between the civilian draftees of 4077th – Hawkeye, Trapper John, and B.J. Hunnicutt, for example – who are forced to leave their homes to tend the wounded and dying of the war, and the "regular Army" characters, such as Margaret Houlihan and Colonel Potter, who tend to represent ideas of patriotism and duty (though Houlihan and Potter could represent the other perspective at times, as well). Other characters, such as Col. Blake, Maj. Winchester, and Cpl. Klinger, help demonstrate various American civilian attitudes toward army life, while guest characters played by such actors as Eldon Quick, Herb Voland, Mary Wickes, and Tim O'Connor also help further the show's discussion of America's place as Cold War warmaker and peacemaker.

Characters

Main cast

M*A*S*H maintained a relatively constant ensemble cast, with four characters – Hawkeye, Father Mulcahy, Margaret Houlihan, and Max Klinger – on the show for all 11 seasons. Several other main characters departed or joined the program midway through its run. Also, numerous guest actors and recurring characters were used. The writers found creating so many names difficult, and used names from elsewhere; for example, characters on the seventh season were named after the 1978 Los Angeles Dodgers.[1]- Note: Character appearances include double-length episodes as two appearances, making 260 in total.

| Character | Actor/actress | Rank | Role | Appearances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawkeye Pierce | Alan Alda | Captain | Chief surgeon | 251 |

| Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan | Loretta Swit | Major | Head nurse, temporary adjutant |

243 |

| Max Klinger (Recurring seasons 1–3, regular 4–11) |

Jamie Farr | Corporal, later sergeant |

Corpsman, later company clerk |

219 |

| Father Mulcahy (recurring seasons 1–4, regular 5–11) |

George Morgan (pilot episode), replaced by William Christopher | First lieutenant, later captain |

Chaplain | 218 |

| Trapper John McIntyre (seasons 1–3) |

Wayne Rogers | Captain | Surgeon | 72 + 1 uncredited voiceover ("Welcome to Korea") |

| Henry Blake (seasons 1–3) |

McLean Stevenson | Lieutenant colonel | Commanding officer, surgeon |

70 |

| Frank Burns (seasons 1–5) |

Larry Linville | Major, later lieutenant colonel (off-screen) |

Surgeon, executive officer temporary commanding officer (following the death of Henry Blake) |

118 |

| Radar O'Reilly (seasons 1–8) |

Gary Burghoff | Corporal (one episode as second lieutenant due to falsified promotion) |

Company clerk, bugler |

156 |

| B. J. Hunnicutt (replaced Trapper; seasons 4–11) |

Mike Farrell | Captain | Surgeon | 187 |

| Sherman Potter (replaced Henry Blake; Seasons 4–11) |

Harry Morgan | Colonel | Commanding officer (after Lt. Col. Blake), surgeon |

188 |

| Charles Emerson Winchester III (replaced Frank Burns; seasons 6–11) |

David Ogden Stiers | Major | Surgeon, executive officer (after Major Burns) | 137 |

Main character timeline

Cast pictures

-

The cast of M*A*S*H from Season 2, 1974 (clockwise from left): Loretta Swit, Larry Linville, Wayne Rogers, Gary Burghoff, McLean Stevenson, and Alan Alda

-

The cast of M*A*S*H from Season 5, 1977 (clockwise from left): William Christopher, Gary Burghoff, David Ogden Stiers, Jamie Farr, Mike Farrell, Alan Alda, Harry Morgan, Loretta Swit.

-

The cast of M*A*S*H from season 8 onwards (clockwise from left): Mike Farrell, William Christopher, Jamie Farr, David Ogden Stiers, Loretta Swit, Alan Alda, and Harry Morgan

Character development

|

This section, on down, needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

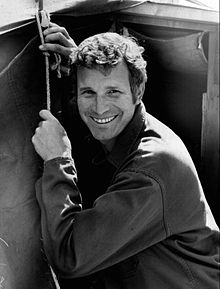

- Captain Benjamin Franklin "Hawkeye" Pierce

Alan Alda as Hawkeye

He attended Androscoggin College. In the book and the film, Hawkeye had played football in college; in the series, he is non-athletic. After completing his medical residency, he was drafted into the U.S. Army Medical Corps and sent to serve at the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) during the Korean War, an assignment he openly resents. Alda said of Pierce, "Some people think he was very liberal. But he was also a traditional conservative. I mean, he wanted nothing more than to have people leave him alone so he could enjoy his martini, you know? Government should get out of his liquor cabinet".[4]

Pierce has little tolerance for military red tape and customs, feeling they get in the way of his doing his job, and has little respect for most Regular Army personnel. He never wears rank insignia on his fatigues, never polishes his combat boots, and on the rare occasions he wears his Class A uniform, does not wear any of the decorations to which he is entitled (which include the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean War Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, a couple of Army commendation medals, and the Army Distinguished Unit Citation,[5] four Purple Hearts, and the Combat Medical Badge). On occasions, he assumes temporary command of the 4077th due to the absence or disability of Colonel Blake or Colonel Potter. Although he acquits himself well, it is plain he is not comfortable with the responsibility that goes with being the commanding officer.

As a surgeon, he does not like the use of firearms. He refuses to carry a sidearm as required by regulations when serving as Officer of the Day.[6] When ordered by Col. Potter to carry his issue pistol on a trip to an aid station, and they are ambushed on the road, he fires it into the air rather than at their attackers.[7]

In the series finale, "Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen", Hawkeye experiences a mental breakdown when a Korean woman responds to his frantic demand that she quiet her infant child lest enemy soldiers hear it and discover them, by suffocating it. When the Korean Armistice is announced, he states his intention to return to Crabapple Cove, to be a local doctor who has the time to get to know his patients, instead of contending with the endless flow of casualties he faced during his time in Korea. In Hooker's two sequels, M*A*S*H Goes to Maine and M*A*S*H Mania, Hawkeye returns to live in Crabapple Cove.

- "Trapper" John McIntyre

Wayne Rogers as Trapper John

Rogers's replacement, Mike Farrell, was hastily recruited during the 1975 summer production hiatus. In the season's first episode, "Welcome to Korea", Hawkeye is informed by Radar that Trapper was transferred to a "stateside" assignment while Hawkeye was on leave, and B.J. Hunnicutt is Trapper's replacement. Trapper was described by Radar as being so jubilant over his release that "he got drunk for two days, and then he ran naked through the mess tent with no clothes on." He made Radar promise to give Hawkeye a kiss as a final farewell message.

Actor Pernell Roberts later played a middle-aged Trapper in the seven-year run of Trapper John, M.D.

- Margaret Houlihan

Loretta Swit as Margaret Houlihan

- Frank Burns

Larry Linville Major as Frank Burns

Frank Burns had four different middle names during his time on the show: W. (on the punching bag in "Requiem for a Lightweight"), D., X., and Marion.

- Radar O'Reilly

Gary Burghoff as Radar O'Reilly

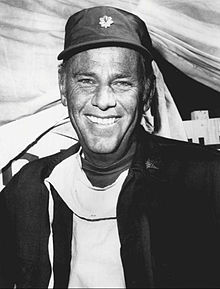

- Henry Blake

McLean Stevenson as Henry Blake

- Max Klinger

Jamie Farr as Max Klinger

Throughout the series, Klinger frequently introduces himself by his full name, Maxwell Q. Klinger, but never says what the Q. stands for.

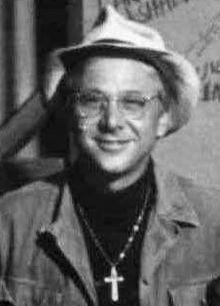

- Father Francis Mulcahy

William Christopher as Father Mulcahy

In the finale ("Goodbye, Farewell and Amen"), Father Mulcahy tells Klinger that his full name is Francis John Patrick Mulcahy, in case Klinger might want to name any of his children after him. Also, in the eighth-season episode "Nurse Doctor", he gives his full name as Francis John Patrick Mulcahy. Yet, in all other episodes, his name was John Patrick Francis Mulcahy, and he just wanted others to call him by his confirmation name, Francis.

- B.J. Hunnicutt

Mike Farrell as B.J. Hunnicutt

- Sherman T. Potter

Harry Morgan as Colonel Potter

Colonel Potter is a regular Army man, having served in both World War I and World War II, first in the cavalry and later as a doctor. He is passionate about horses, and keeps an old US Cavalry issue McClellan saddle in his office, which is later put to use when he acquires a horse, when Radar gives one to him for his wedding anniversary, after B.J. and Hawkeye are unable to catch it. This horse, which remained with Col. Potter until the end of the series, was referred to as a colt (Potter remarks, "He can't be more than four years old") in its first appearance, after which it is named "Sophie" and referred to as a mare. In his spare time, Potter also enjoys painting.

- Charles Emerson Winchester III

David Ogden Stiers as Charles Emerson Winchester III

Winchester was respected by the others professionally, but at the same time, as a Boston blue blood, he was also snobbish, as when he stated in the scrub room, "I do one thing at a time, I do it very well, and then I move on," which drove much of his conflict with the other characters. Still, the show's writers occasionally allowed Winchester's humanity to shine through, such as in his dealings with a young concert pianist who had partially lost the use of his right hand, the protection of a stuttering soldier from the bullying of other soldiers (it is revealed later that Winchester's sister Honoria stutters),[10] his keeping a vigil with Hawkeye when Hawkeye's father went into surgery back in the States ("Sons and Bowlers"), his willingness to be officer of the day for Hawkeye when Hawkeye was offered three days in Seoul, giving blood to a patient even though he already donated blood five days earlier, or his continuing a family tradition of anonymously giving Christmas treats to an orphanage. Winchester subjects himself to condemnation after realizing that "it is sadly inappropriate to offer dessert to a child who has had no meal." Isolating himself, he is saved by Klinger's own gift of understanding. Klinger scrapes together a Christmas dinner for Charles, with the provision that the source of the gift remain anonymous (Klinger had overheard Winchester's argument with the manager of the orphanage). For the final moment of the episode ("Death Takes a Holiday"), the two are simply friends as Charles says, "Thank you, Max," and Klinger replies, "Merry Christmas, Charles." As well, in the series finale "Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen", Charles comes across a group of Chinese musicians who surrender to him. When Charles takes them back to the camp as prisoners of war and later listens to his record of Mozart's Quintet in A major for Clarinet and Strings, K. 581, the musicians attempt to play the piece of music. Charles, ever the perfectionist, cannot stand to hear them play the piece incorrectly (and is impressed that they can even attempt to play the music after only hearing it once) and spends the next week conducting them on how to play the piece properly. During this time, Charles is forced to use the little patience that he rarely shows. When the Chinese musicians are taken off to a prisoner of war camp in a prisoner exchange to Charles' dismay and protest, their final goodbye to Charles is the Mozart piece played correctly. Later, one of the musicians returns to the camp mortally wounded on a Jeep. When Charles inquires as to where the other musicians are, it's revealed that the truck the musicians were on was ambushed and that there were no other survivors. In a combination of shock and disbelief, Charles returns to The Swamp to listen to the Mozart record, but removes the record and smashes it in anger. Later still on the final night that everyone at the M*A*S*H is together, Charles says that before the war, music was a stress reliever to him, but because of the Chinese musicians and their fate, music will forever be a reminder of the horrors of war.

Character injuries

|

This section does not cite any sources. (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Among those wounded were Hawkeye Pierce ("Hawkeye", "Out of Sight, Out of Mind", "Comrades in Arms [Part I]", "Good-Bye, Radar [Part I]", and "Lend a Hand"), Radar O'Reilly ("Fallen Idol"), B.J. Hunnicutt ("The Abduction of Margaret Houlihan" and "Operation Friendship"), Max Klinger ("It Happened One Night", "Baby, It's Cold Outside", and "Operation Friendship"), Father Mulcahy ("Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" and "Bombed"), and Sherman Potter ("Dear Ma"). Henry Blake was injured four times: once by a disgruntled chopper pilot ("Cowboy"), once by friendly fire ("The Army-Navy Game"), and in season 3, episode 15 ("Bombed"), Henry is injured when he is blown up while in the latrine. (The gag of Blake being caught in an exploding latrine is also in the episode "Cowboy".) Henry is also injured when the latrine catches fire. Father Mulcahy is given a concussion on two separate occasions – first in the episode "Bombed", where he is in the latrine stall next to Blake when it is blown up; and again in "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" when he is knocked out by mortar fire which strikes close by him; he also suffers severe hearing loss as a result of this incident. Frank Burns is twice awarded Purple Hearts for spurious injuries: throwing his back out after he gave Margaret a dip and could not move – which was later covered up with a story that he slipped on the way to the showers ("Sometimes You Hear the Bullet", 1.17), and getting an egg-shell fragment in the eye ("The Kids", 4.8). Burns' Purple Heart medals were then given to more deserving people: a GI who was admitted with appendicitis and a Korean newborn infant who was hit by a bullet in utero.

At least three permanent 4077 personnel suffered emotional breakdowns: Hawkeye Pierce ("Goodbye, Farewell and Amen"), B.J. Hunnicutt ("Period of Adjustment"), and Frank Burns ("Fade Out, Fade In").

Guest cast

Production

Writing

As the series progressed, it made a significant shift from being primarily a comedy with dramatic undertones to a drama with comedic undertones. This was a result of changes in writing and production staff, rather than the cast defections of McLean Stevenson, Larry Linville, Wayne Rogers and Gary Burghoff. Series co-creator and joke writer Larry Gelbart departed after Season 4, the first featuring Mike Farrell and Harry Morgan. This resulted in Farrell and Morgan having only a single season reading scripts featuring Gelbart's masterful comic timing, which defined the feel and rhythm of Seasons 1–4 featuring predecessors Rogers and Stevenson, respectively. Larry Linville (the show's comic foil) and Executive Producer Gene Reynolds both departed at the conclusion of Season 5 in 1977, resulting in M*A*S*H being fully stripped of its original tight comedic foundation by the beginning of Season 6 — the debut of the Charles Winchester era.[8]Whereas Gelbart and Reynolds were the comedic voice of M*A*S*H for the show's first five seasons (1972–1977), Alan Alda and newly promoted Executive Producer Burt Metcalfe became the new dramatic voice of M*A*S*H for Seasons 6–11. By the start of Season 8 (1979–1980), the writing staff had been completely overhauled, and with the departure of Gary Burghoff, M*A*S*H displayed a distinctively different feel, consciously moving between comedy and drama, unlike the seamless integration of its first five years.

The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 was a significant factor as to why storylines become less political in nature and more character driven. Several episodes also experimented with the sitcom format:

- "Point of View" – shown from the perspective of a soldier with a throat wound

- "Dreams" – an idea of Alda's, where during a deluge of casualties, members of the 4077 take naps on a rotation basis, allowing the viewer to see the simultaneously lyrical and disturbing dreams

- "A War For All Seasons" – features a storyline that takes place over the course of 1951

- "Life Time" – a precursor to the American television series 24, it utilizes the real time method of narration[8]

While the series remained popular through these changes, it eventually began to run out of creative steam. Korean War doctors regularly contacted producers with experiences that they thought might make for a good storyline, only to learn the idea had previously been used. Harry Morgan admitted that he felt "the cracks were starting to show" by season 9 (1980–1981).[8] Alda wished to make season 10 (1981-1982) M*A*S*H's last, but was persuaded by CBS to produce a slightly shortened 11th season, coupled with a farewell movie finale, because CBS refused to let the show go away so easily. In the end, season 11 had 15 episodes (although six had been filmed during season 10 and held over) and a 2-1/2 hour movie, which was treated as five episodes and was filmed before the nine remaining episodes. The final episode ever produced was the penultimate episode "As Time Goes By". The series finale movie, titled "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen", became the most-watched television broadcast in history, tallying a total of 125 million viewers.[8]

Set location

M*A*S*H site in Malibu Creek State Park. Hulk of a Dodge WC54 ambulance.

Copy of the original M*A*S*H signpost was installed on the site in

2008.

Just as the series was wrapping production, a brush fire destroyed most of the outdoor set on October 9, 1982. The fire was written into the final episode as a forest fire caused by enemy incendiary bombs that forced the 4077th to bug out.

The Malibu location is today known as Malibu Creek State Park. Formerly called the Century Ranch and owned by 20th Century Fox Studios until the 1980s, the site today is returning to a natural state, and is marked by a rusted Jeep and an ambulance used in the show. Through the 1990s, the area was occasionally used for television commercial production.

On February 23, 2008, series stars Mike Farrell, Loretta Swit and William Christopher (along with producers Gene Reynolds and Burt Metcalfe and M*A*S*H director Charles S. Dubin) reunited at the set to celebrate its partial restoration. The rebuilt signpost is now displayed on weekends, along with tent markers and maps and photos of the set. The state park is open to the public. It was also the location where the film How Green Was My Valley (1941) and the Planet of the Apes television series (1974) were filmed, among other productions.

Smithsonian exhibit

The operating room set on display in the National Museum of American History as part of the "MASH: Binding Up the Wounds" exhibit in 1983

On exhibit were The Swamp and Operating Room sets, one of the show's 14 Emmy Awards, early drafts of the pilot script, costumes from the show and other memorabilia. Sets were decorated with props from the show including the iconic signpost, Hawkeye's still and Major Winchester's Webcor tape recorder and phonograph. The exhibit also encouraged visitors to compare the show to real Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals of the Korean and the Vietnam Wars. [12][13]

Radar's teddy bear, originally found at the ranch set, was never on display at the Smithsonian. Following completion of production, the prop was kept by the show's set designer. It was sold several times including to Burghoff himself.[14] It was sold at auction on July 29, 2005 for $11,800, it sold again on March 27, 2015 for $14,307.50 after 19 bids.[15]

Content

M*A*S*H was one of the first network series to feature brief partial nudity (notably Gary Burghoff's buttocks in "The Sniper" and Hawkeye in one of the "Dear Dad" episodes). A different innovation was the show's producers' desire not to have a laugh track, contrary to the network's desire to have one. They compromised by omitting laughter in the scenes set in the operating room. The DVD releases of the series allow viewers to select an audio version with no laugh track.In his blog, writer Ken Levine revealed that on one occasion, when the cast offered too many nitpicking "notes" on a script, his writing partner and he changed the script to a "cold show" – one set during the frigid Korean winter. The cast then had to stand around barrel fires in parkas at the Malibu ranch when the temperatures neared 100 °F (38 °C). Levine says, "This happened maybe twice, and we never got a ticky-tack note again."[16]

Jackie Cooper wrote that Alan Alda, whom Cooper directed in several episodes during the first two seasons, concealed a lot of hostility beneath the surface, and the two of them barely spoke to each other by the time Cooper's tenure on the show ended.[17]

Vehicles

The helicopters used on the series were model H-13 Sioux (military designation and nickname of the Bell 47 civilian model). As in the film, some care seems to have been taken to use the correct model of the long-lived Bell 47 series. In the opening credits and many of the episodes, Korean War-vintage H-13Ds and Es (Bell 47D-1s) were used complete with period-correct external litters. A later (1954–73) 47G occasionally made an appearance. The helicopters are similar in appearance (with the later "G" models having larger two-piece fuel tanks, a slightly revised cabin, and other changes) with differences noticeable only to a serious helicopter fan. In the pilot episode, a later Bell 47J (production began in 1957) was shown flying Henry Blake to Seoul, en route to a meeting with General Hammond in Tokyo.[18] A Sud Aviation Allouette II helicopter was also shown transporting Henry Blake to the 4077th in the episode "Henry, Please Come Home".The Jeeps used were 1953 military M38 or civil CJ2A Willys Jeeps and also World War II Ford GPWs and Willys MB's. Two episodes featured the M38A1 Jeep, one of which was stolen from a General by Radar and Hawkeye after their Jeep was stolen. Two of the ambulances were WC-54 Dodges and one was a WC-27. A WC-54 ambulance remains at the site and was burned in the Malibu fires on October 9, 1982, while a second WC-27 survives at a South El Monte museum without any markings. The bus used to transport the wounded was a 1954 Ford model. In the last season, an M43 ambulance from the Korean War era also was used in conjunction with the WC-54s and WC-27.

Laugh track

Series creators Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds wanted M*A*S*H broadcast without a laugh track ("Just like the actual Korean War", he remarked dryly). Though CBS initially rejected the idea, a compromise was reached that allowed for omitting the laughter during operating room scenes if desired. Seasons 1–5 utilized a more invasive laugh track; a more subdued audience was employed for Seasons 6–11 when the series shifted from sitcom to comedy-drama with the departure of Gelbart and Reynolds. Several episodes ("O.R.", "The Bus", "Quo Vadis, Captain Chandler?", "The Interview", "Point of View" and "Dreams" among them) omitted the laugh track altogether; as did almost all of Season 11, including the 135-minute series finale, "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen".[19] The laugh track is also omitted from some international and syndicated airings of the show; on one occasion during an airing on BBC2, the laugh track was accidentally left on, and viewers expressed their displeasure, an apology from the network for the "technical difficulty" was later released, as during its original run on BBC2 in the UK, it was shown without the laugh track. UK DVD critics speak poorly of the laugh track, stating "canned laughter is intrusive at the best of times, but with a programme like M*A*S*H, it's downright unbearable."[20]On all released DVDs, both in Region 1 (including the U.S. and Canada) and Region 2 (Europe, including the UK), an option is given to watch the show with or without the laugh track.[21][22]

"They're a lie," said Gelbart in a 1992 interview. "You're telling an engineer when to push a button to produce a laugh from people who don't exist. It's just so dishonest. The biggest shows when we were on the air were All in the Family and The Mary Tyler Moore Show both of which were taped before a live studio audience where laughter made sense," continued Gelbart. "But our show was a film show – supposedly shot in the middle of Korea. So the question I always asked the network was, 'Who are these laughing people? Where did they come from?'" Gelbart persuaded CBS to test the show in private screenings with and without the laugh track. The results showed no measurable difference in the audience's enjoyment. "So you know what they said?" Gelbart said. "'Since there's no difference, let's leave it alone!' The people who defend laugh tracks have no sense of humor."[19] Gelbart summed up the situation by saying, "I always thought it cheapened the show. The network got their way. They were paying for dinner."[23]

Episodes

Episode list

| Season | Episodes | Originally aired | Nielsen ratings[24] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aired | Last aired | Rank | Rating | ||||

| 1 | 24 | September 17, 1972 | March 25, 1973 | N/A | N/A | ||

| 2 | 24 | September 15, 1973 | March 2, 1974 | 4 | 25.7 | ||

| 3 | 24 | September 10, 1974 | March 18, 1975 | 5 | 27.4 | ||

| 4 | 25 | September 12, 1975 | February 24, 1976 | 14 | 22.9[b] | ||

| 5 | 25 | September 21, 1976 | March 15, 1977 | 4 | 25.9 | ||

| 6 | 25 | September 20, 1977 | March 27, 1978 | 8 | 23.2[c] | ||

| 7 | 26 | September 18, 1978 | March 12, 1979 | 7 | 25.4 | ||

| 8 | 25 | September 17, 1979 | March 24, 1980 | 4 | 25.3[c] | ||

| 9 | 20 | November 17, 1980 | May 4, 1981 | 4 | 25.7 | ||

| 10 | 22 | October 26, 1981 | April 12, 1982 | 9 | 22.3 | ||

| 11 | 16 | October 25, 1982 | February 28, 1983 | 3 | 22.6[d] | ||

- Tied with Magnum, P.I.

Final episode: "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen"

"Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" was the final episode of M*A*S*H. Special television sets were placed in PX parking lots, auditoriums, and dayrooms of the U.S. Army in Korea so that military personnel could watch that episode, in spite of 14 hours' time-zone difference with the East Coast of the U.S. The episode aired on February 28, 1983, and was 2½ hours long. The episode got a Nielsen rating of 60.2 and 77 share[25] and according to a New York Times article from 1983, the final episode of M*A*S*H had 125 million viewers.[26]When the M*A*S*H finale aired in 1983, 83.3 million homes in the United States had televisions, compared to almost 115 million in February 2010.[27]

"Goodbye, Farewell and Amen" broke the record for the highest percentage of homes with television sets to watch a television series. Stories persist that the episode was seen by so many people that the New York City Sanitation/Public Works Department reported the plumbing systems broke down in some parts of the city from so many New Yorkers waiting until the end to use the toilet. Articles copied into Alan Alda's book The Last Days of M*A*S*H include interviews with New York City Sanitation workers citing the spike in water use on that night. According to the interviews at 11:03 pm, EST New York City public works noted the highest water usage at one given time in the City's history. They attributed this to the fact that in the three minutes after the finale ended, around 77% of the people of New York City flushed their toilets.[28] These stories have all since been identified as part of an urban legend dating back to the days of the Amos and Andy radio program in the 1930s.[29]

The finale was referenced in a passage from Stephen Chbosky's coming-of-age novel The Perks of Being a Wallflower, in which the main character and his family watch the finale together.[30]

International broadcast

- Australia - Network Ten (1973–1998), Seven Network (1999–2011), One (2011–2017), 7TWO (2018–)

- UK - BBC Two - (1984-1995)

- Ireland - RTÉ2 - (1985-1996)

Reception

Ratings and recognition

The series premiered in the U.S. on September 17, 1972, and ended on February 28, 1983, with the finale, showcased as a television film, titled "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen", becoming the most-watched and highest-rated single television episode in U.S. television history at the time, with a record-breaking 125 million viewers (60.2 rating and 77 share),[31] according to the New York Times.[26] It had struggled in its first season and was at risk of being cancelled.[32] Season two of M*A*S*H placed it in a better time slot (airing after the popular All in the Family); the show became one of the top 10 programs of the year and stayed in the top 20 programs for the rest of its run.[32] It is still broadcast in syndication on various television stations. The series, which depicted events occurring during a three-year war, spanned 256 episodes and lasted 11 seasons. The Korean War lasted 1,128 days, meaning each episode of the series would have averaged almost four and a half days of real time. Many of the stories in the early seasons are based on tales told by real MASH surgeons who were interviewed by the production team. Like the movie, the series was as much an allegory about the Vietnam War (still in progress when the show began) as it was about the Korean War.[33]The episodes "Abyssinia, Henry" and "The Interview" were ranked number 20 and number 80, respectively, on TV Guide's 100 Greatest Episodes of All Time in 1997.[34] In 2002, M*A*S*H was ranked number 25 on TV Guide's 50 Greatest TV Shows of All Time.[35] In 2013, the Writers Guild of America ranked it as the fifth-best written TV series ever[36] and TV Guide ranked it as the eighth-greatest show of all time.[37] In 2016, Rolling Stone ranked it as the sixteenth-greatest TV show.[38]

Season ratings

| Season | Ep # | Time slot (ET) | Season Premiere | Season Finale | Nielsen Ratings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Viewers (in millions) |

Rating | ||||||

| 1 | 1972–73 | 24 | Sunday at 8:00 pm | September 17, 1972 | March 25, 1973 | #46[39] | N/A | 17.4 |

| 2 | 1973–74 | 24 | Saturday at 8:30 pm | September 15, 1973 | March 2, 1974 | #4[40] | 17.02[40] | 25.7 |

| 3 | 1974–75 | 24 | Tuesday at 8:30 pm | September 10, 1974 | March 18, 1975 | #5[41] | 18.76[41] | 27.4 |

| 4 | 1975–76 | 25 | Friday at 8:00 pm (Episode 1) Friday at 8:30 pm (Episodes 2–13) Tuesday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 14–25) |

September 12, 1975 | February 24, 1976 | #15[42] | 15.93[42] | 22.9 |

| 5 | 1976–77 | 25 | Tuesday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 1, 3–25) Tuesday at 9:30 pm (Episode 2) |

September 21, 1976 | March 15, 1977 | #4[43] | 18.44[43] | 25.9 |

| 6 | 1977–78 | 25 | Tuesday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 1, 3–19) Tuesday at 9:30 pm (Episode 2) Monday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 20–25) |

September 20, 1977 | March 27, 1978 | #9[44] | 16.91[44] | 23.2 |

| 7 | 1978–79 | 26 | Monday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 1–4, 6–26) Monday at 9:30 pm (Episode 5) |

September 18, 1978 | March 12, 1979 | #7[45] | 18.92[45] | 25.4 |

| 8 | 1979–80 | 25 | Monday at 9:00 pm | September 17, 1979 | March 24, 1980 | #5[46] | 19.30[46] | 25.3 |

| 9 | 1980–81 | 20 | November 17, 1980 | May 4, 1981 | #4[47] | 20.53[47] | 25.7 | |

| 10 | 1981–82 | 22 | Monday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 1, 3–22) Monday at 9:30 pm (Episode 2) |

October 26, 1981 | April 12, 1982 | #9[48] | 18.17[48] | 22.3 |

| 11 | 1982–83 | 16 | Monday at 9:00 pm (Episodes 1–15) Monday at 8:30 pm (Episode 16) |

October 25, 1982 | February 28, 1983 | #3[49] | 18.82[49] | 22.6 |

Awards

M*A*S*H was nominated for over 100 Emmy Awards during its 11-year run, winning 14:- 1974 – Outstanding Comedy Series – M*A*S*H; Larry Gelbart, Gene Reynolds (Producers)

- 1974 – Best Lead Actor in a Comedy Series – Alan Alda

- 1974 – Best Directing in Comedy – Jackie Cooper: "Carry On, Hawkeye"

- 1974 – Actor of the Year, Series – Alan Alda

- 1975 – Outstanding Directing in a Comedy Series – Gene Reynolds: "O.R."

- 1976 – Outstanding Film Editing for Entertainment Programming – Fred W. Berger and Stanford Tischler: "Welcome to Korea"

- 1976 – Outstanding Directing in a Comedy Series – Gene Reynolds: "Welcome to Korea"

- 1977 – Outstanding Directing in a Comedy Series – Alan Alda: "Dear Sigmund"

- 1977 – Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series – Gary Burghoff

- 1979 – Outstanding Writing in a Comedy-Variety or Music Series – Alan Alda: "Inga"

- 1980 – Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy or Variety or Music Series – Loretta Swit

- 1980 – Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy or Variety or Music Series – Harry Morgan

- 1982 – Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series – Alan Alda

- 1982 – Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy or Variety or Music Series – Loretta Swit

The series earned the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in a Comedy Series seven times: 1973 (Gene Reynolds), 1974 (Reynolds), 1975 (Hy Averbeck), 1976 (Averbeck), 1977 (Alan Alda), 1982 (Alda), 1983 (Alda).

The show was honored with a Peabody Award in 1975 "for the depth of its humor and the manner in which comedy is used to lift the spirit and, as well, to offer a profound statement on the nature of war." M*A*S*H was cited as "an example of television of high purpose that reveals in universal terms a time and place with such affecting clarity."[50]

Writers for the show received several Humanitas Prize nominations, with Larry Gelbart winning in 1976, Alan Alda winning in 1980, and the team of David Pollock and Elias Davis winning twice in 1982 and 1983.

The series received 28 Writers Guild of America Award nominations – 26 for Episodic Comedy and two for Episodic Drama. Seven episodes won for Episodic Comedy in 1973, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1979, 1980, and 1981.

Home media

20th Century Fox Home Entertainment has released all 11 seasons of M*A*S*H on DVD in Region 1 and Region 2.| DVD title | Ep No. | Release dates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Region 2 | |||

| M*A*S*H Season 1 | 24 | January 8, 2002 | May 19, 2003 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 2 | 24 | July 23, 2002 | October 13, 2003 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 3 | 24 | February 18, 2003 | March 15, 2004 | |

| M*A*S*H Seasons 1–3 | 72 | N/A | October 31, 2005 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 4 | 24 | July 15, 2003 | June 14, 2004 | |

| M*A*S*H Seasons 1–4 | 96 | December 2, 2003 | N/A | |

| M*A*S*H Season 5 | 24 | December 9, 2003 | January 17, 2005 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 6 | 24 | June 8, 2004 | March 28, 2005 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 7 | 25 | December 7, 2004 | May 30, 2005 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 8 | 25 | May 24, 2005 | August 15, 2005 | |

| M*A*S*H Season 9 | 20 | December 6, 2005 | January 9, 2006 | |

| M*A*S*H Seasons 1–9 | 214 | December 6, 2005 | N/A | |

| M*A*S*H Season 10 | 22 | May 23, 2006 | April 17, 2006 | |

No comments:

Post a Comment